I realized that getting a good grasp on intervals was a valuable tool because different intervals are the underpinning of both melody and the chords over which melodies are played. A harmonic interval is the basis of chords and chord structure. They form the different major and minor chords. Melodic intervals build the different melodies in music. What does this mean for you as a player?

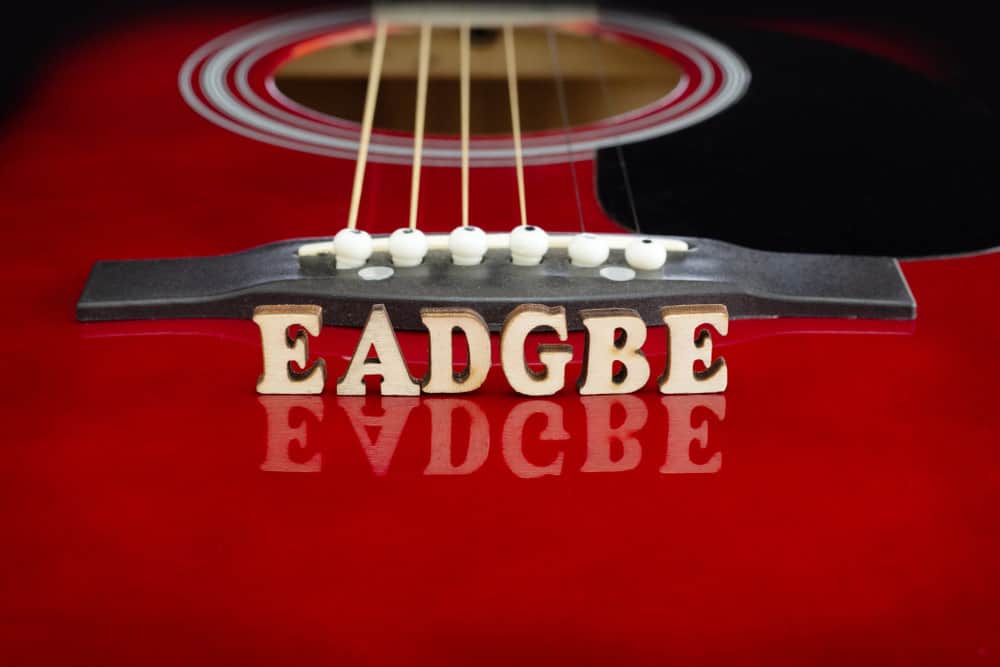

According to Eddie Van Halen, “A guitar is just theoretically built wrong. Each string is an interval of fourths, and then the B string is off. Theoretically, that’s not right; all the strings should be off.” There is an answer to Eddie’s question about the guitar being “built wrong” that he knew for certain and which we explain to you in this article.

Gary Marcus, the author of Guitar Zero, also said, “Nobody is born being able to hear intervals, and many people never master them. Some people never even notice that ‘Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star’ and ‘The Alphabet Song’ follow the same melody and consist of the same sequence of intervals.”

A guitar interval is the musical distance between two notes. On the guitar, it is measured as the distance between frets. You use frets to form shapes to play chords. Playing notes on the frets in order forms a melody. Read on to learn more about how intervals on the guitar can help you create the sounds you want to play.

What Are Guitar Intervals?

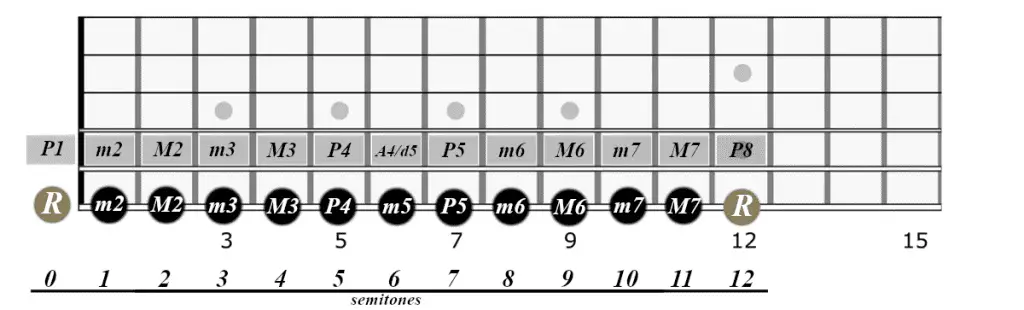

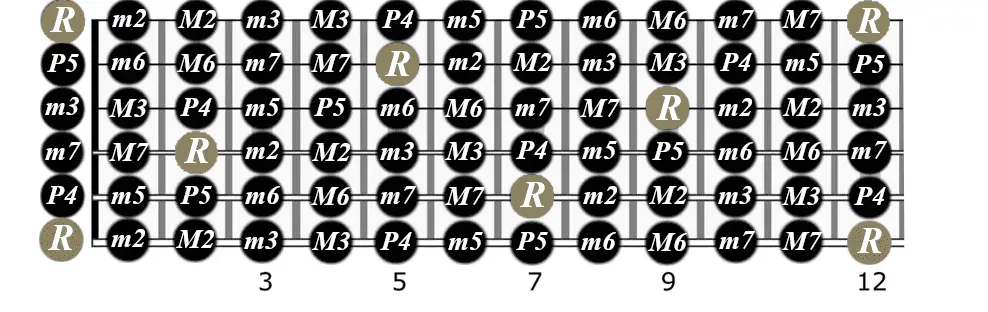

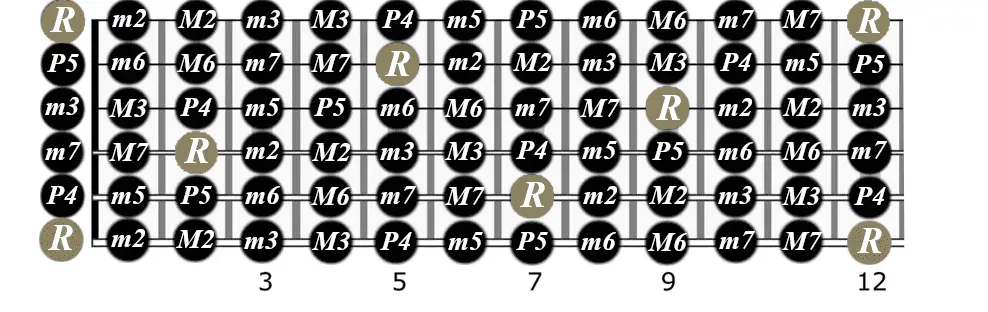

Intervals on the guitar start with a root note, denoted with the symbol “R.” Their minimum size is one semitone—also called a half-tone—and each fret represents a semitone. Intervals form the framework upon which all music is constructed, whether we realize it or not.

Each interval has its own characteristic sound, which conveys a mood or feeling; for example: sad, happy, tense, or relaxed. Intervals can be either melodic, as in a melody the notes are sounded one at a time in succession, or harmonic, where the notes are sounded simultaneously—as in two people singing harmony or in the relationships that form chords. Or, for that matter, as when you play a chord on the guitar.

Interval distance is defined by the number of frets (half-tones or semitones) that separate the notes of the interval and how and when they are played.

Intervals are typically abbreviated using the corresponding letter of the interval quality shown in the Key below the Intervals Chart shown below, along with the number of that note in the 1 thru 8 note scale (e.g. in the Key of C: C=1, D=2, E=3, F=4, G=5, A=6, B=7 and C(octave) = 8). Interval distance can also have an emotional effect on the listener.

Interval distance plays an important role in music theory.

Each fret on the guitar is a semitone. Let’s look first at this chart that shows basic intervals in the chromatic scale for any instrument or voice.

Note: the chart might not make much sense right now if you’re totally new to the concept of intervals. Come back to the chart when you finish reading the article, and it will be perfectly clear!

| Semitones / Half tones | Quality | Abbreviation/Shorthand |

| 0 | Perfect Unison | P1 |

| 1 | Minor 2nd | m2 |

| 2 | Major 2nd | M2 |

| 3 | Minor 3rd | m3 |

| 4 | Major 3rd | M3 |

| 5 | Perfect 4th | P4 |

| 6 | Augmented 4th/Diminished 5th | A4/d5 |

| 7 | Perfect 5th | P5 |

| 8 | Minor 6th | m6 |

| 9 | Major 6th | M6 |

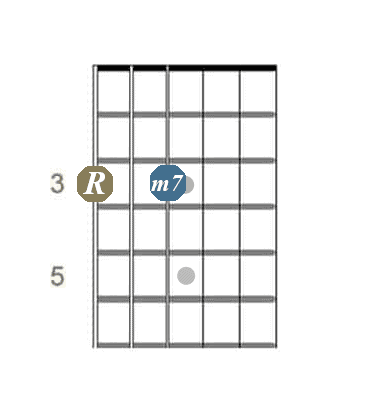

| 10 | Minor 7th | m7 |

| 11 | Major 7th | M7 |

| 12 | Octave | P8 |

Key:

Perfect – P

Minor – m

Major – M

Augmented – A

Diminished – d

Here’s how the intervals look on the low E string for the chromatic scale starting with E as the root note:

And here’s how intervals move and change with the root note moving up and down the neck of the guitar:

We can identify five major diverse interval types or qualities by listening to different intervals and the musical feelings they convey. A different combination of interval notes can create a major scale, a harmonic minor scale, and many other essential aspects of guitar music.

What Are The Primary Types Of Guitar Intervals?

When we’re starting to learn intervals on guitar, the types can become overwhelming. Here’s a concise guide to the different types of intervals on guitar that you can learn:

Perfect Intervals

In a perfect interval, both notes are part of the Major scale (more on this later). The perfect interval has a pleasing or sweet sound. There are four Perfect intervals within the 12 tones of the chromatic scale that comprise an octave.

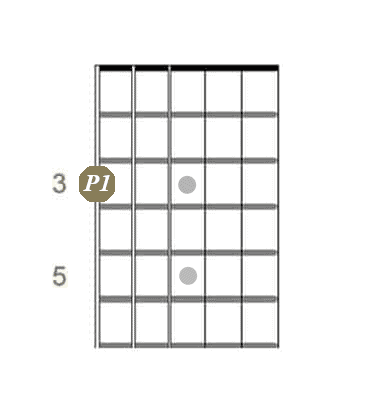

Perfect Unison (P1)

This perfect interval is simply the root note repeated, also known as the same interval. The number of semitones or half-tones separating the root note of the Perfect Unison is, naturally, zero. Therefore, R = P1.

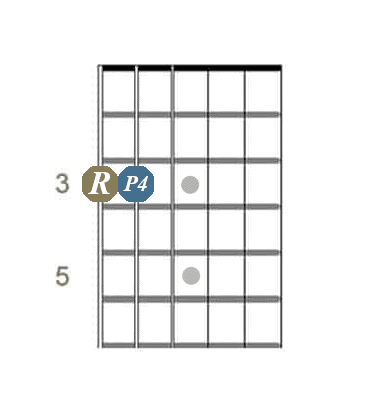

Perfect 4th (P4)

Separated by five frets or semitones. It can be heard in the first two notes of “Here Comes the Bride“.

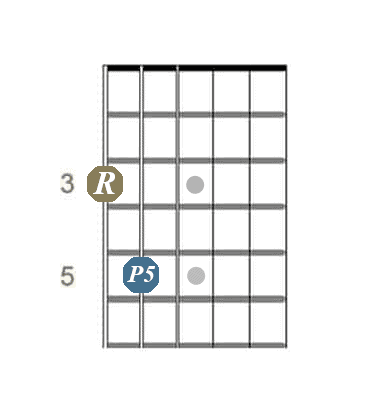

Perfect 5th (P5)

Separated by seven semitones. The Perfect 5th can be heard at the beginning of “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star.” It is the interval between the first and second Twinkle.

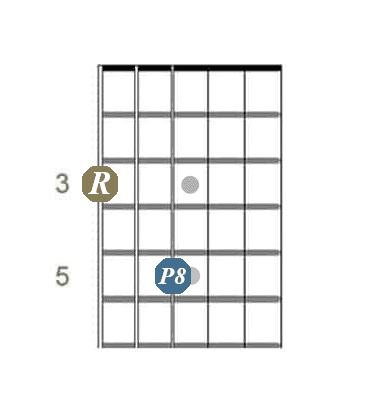

Perfect 8th (Octave, aka P8)

The Perfect 8th or Octave interval is separated by 12 semitones. It is the simplest interval in music after the Perfect Unison (P1). Given a song to sing together, men and women often naturally adopt a style of singing harmony in octaves.

How Do Power Chords Relate to Intervals?

Power chords are the heart and soul of Metal and Heavy Rock of all kinds. Check out the beginning of Good Times Bad Times by Led Zeppelin.

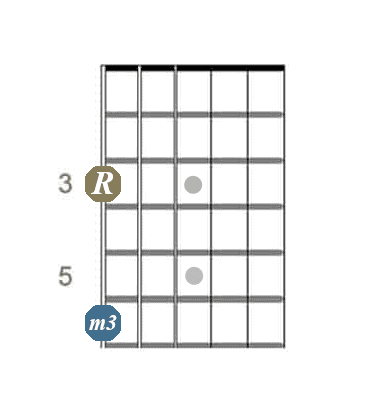

What makes these strong-sounding chords power chords? They only contain the root note and the Perfect 5th (P5). The root and Perfect 5th (P5) interval is likely the interval with which we most universally react.

Thus, when used without the embellishment of a minor 3rd (m3) or Major 3rd (M3) in a chord, our ear is immediately interested. This chord structure tells us to pay attention without reservation.

Power chords on guitar typically stack multiple octaves and Perfect 5ths (p5) to achieve an even more commanding sound. Try building your own power chords by picking a root note and building additional octaves and Perfect 5ths (p5) from that initial root. Happy power playing!

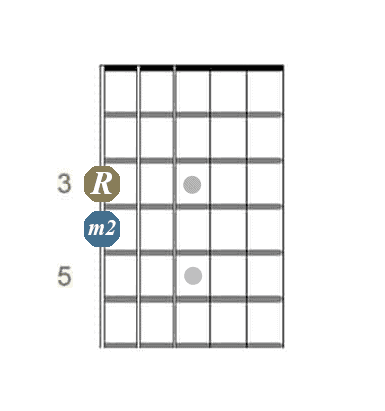

Minor Intervals

Minor intervals are identified in interval charts with a small “m” followed by the interval distance. The minor interval doesn’t generally have a sweet sound like perfect intervals. They can range from two notes only one semitone or half step apart, which creates a disturbing dissonance (m2).

Other minor intervals can reflect from sadness (m3 and m6) to a more pleasant sound (m7). The m2 is one semitone or half-tone interval, m3 is three semitones, m6 is eight semitones, and m7 is ten semitones.

If you’re with me in the “learning intervals for Dummies” game, every time you see “semitone,” think “fret.” A minor interval is an essential part of blues guitar scales and chords. You can also hear the term minor second interval, which is another way to say one half-step, half-tone, or semitone. It is abbreviated as m2.

Major Intervals

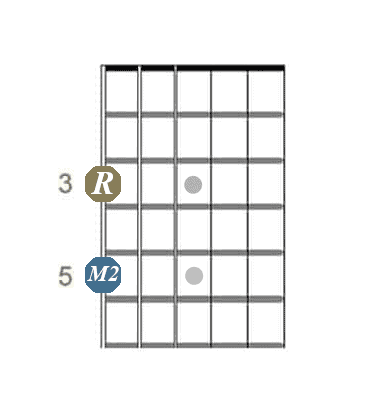

Major intervals are identified in interval charts by a capital “M”, or a triangle (∆) followed by the interval distance. An interval of two semitones is a Major 2nd (M2 or ∆2). This interval sounds somewhat dissonant but much less so that the m2 interval.

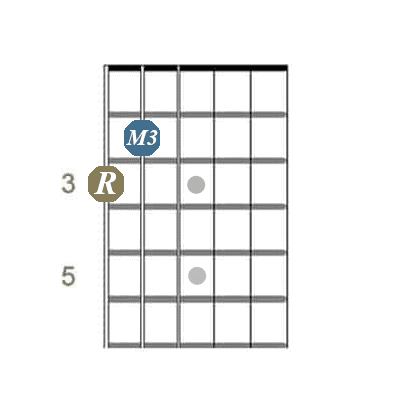

An interval of 4 semitones is a Major 3rd (M3). M3 has a bright, uplifting quality, often described as “happy.”

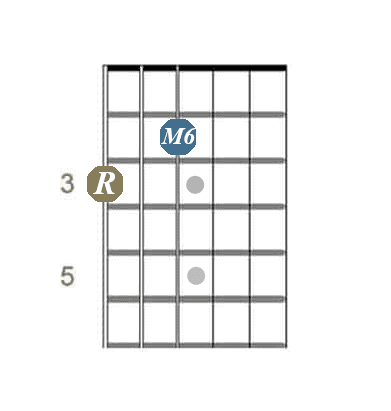

An interval of 9 semitones is a Major 6th (M6). This interval is pleasant and can be heard in the opening notes of “My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean.”

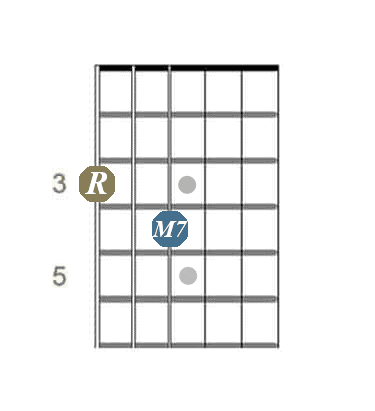

Finally, an interval of 11 semitones is a Major 7th (M7). This interval is considered dissonant in the manner of the minor 2nd (m2), but in fact, its sound is much more pleasant. Actually, you could say it is characteristic of jazz music. Although few examples exist of songs beginning with a Major 7th, there is one good example of this melodic interval structure: the first three notes of “(Somewhere) Over the Rainbow,” which are P1, P8, M7.

Augmented or Diminished

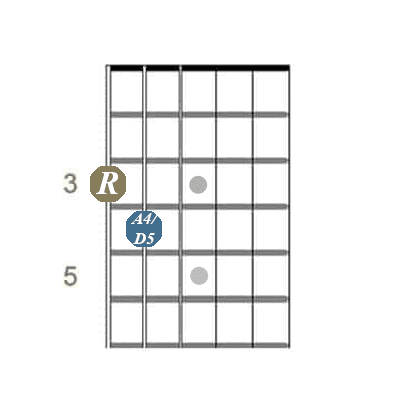

The Augmented 4th/Diminished 5th interval (A4/d5), written with a capital A and a lowercase “d,” is the final interval to discuss. Yes, this is a single interval with two different names.

An Augmented 4th is one semitone higher (up one fret) from a Perfect 4th, and a diminished 5th is one semitone lower than the Perfect 5th. A4/d5 is an interval of 6 semitones or half-tones.

Augmented/diminished intervals sound dissonant and tend to create a sense of tension. You could have heard this type of interval called a tritone because it is comprised of 3 whole tones (6 semitones/half steps). A great example of this interval is the opening notes of “Purple Haze.”

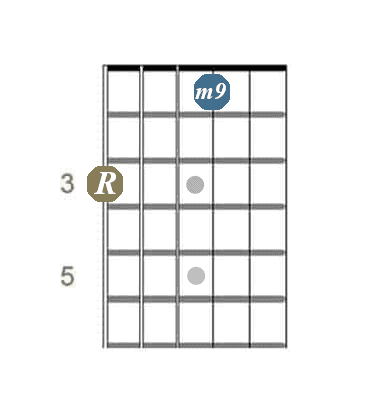

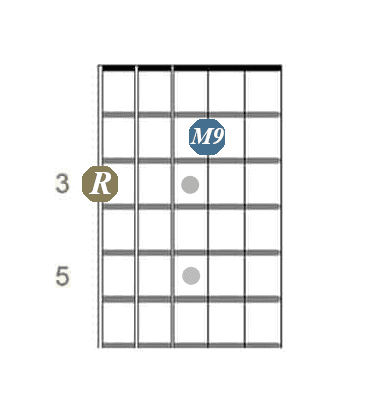

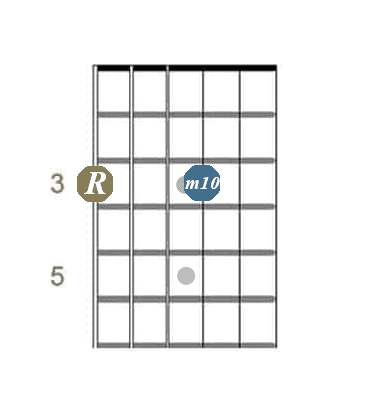

What Are Compound Intervals?

Compound intervals are intervals larger than an octave. Compound intervals are functionally the same as the corresponding simple intervals (those an octave or less in size). Thus, a 9th is a compound 2nd, a 10th is a compound 3rd, an 11th is a compound 4th, a 12th is a compound 5th, and so on.

Compound intervals are used to extend chords beyond the 7th of the base octave to include those intervals created between the Root and the next higher octave. Chords in jazz typically make routine use of harmonic intervals in 9ths, 11ths, and 13ths for chord formation to create sounds richer and more complex than can be achieved using only the base octave. Guitar players can use compound intervals as part of melodic intervals to add exciting leaps of pitch.

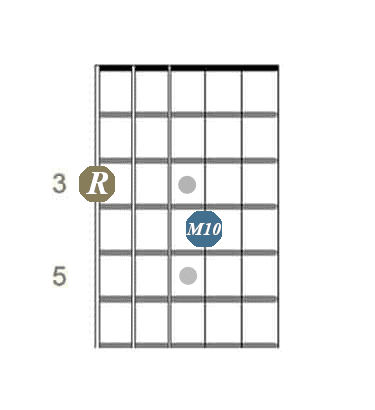

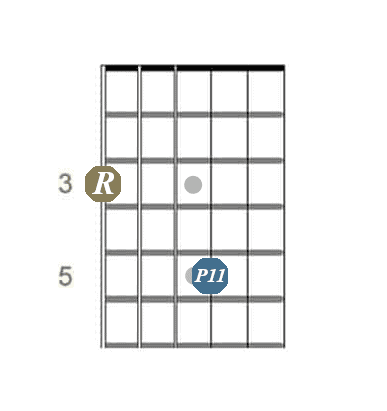

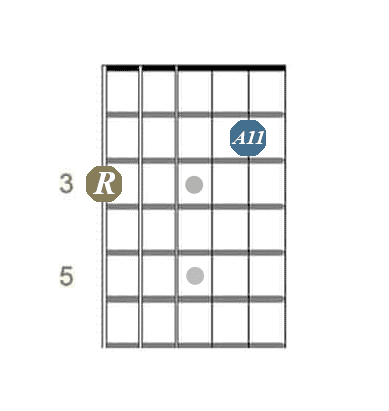

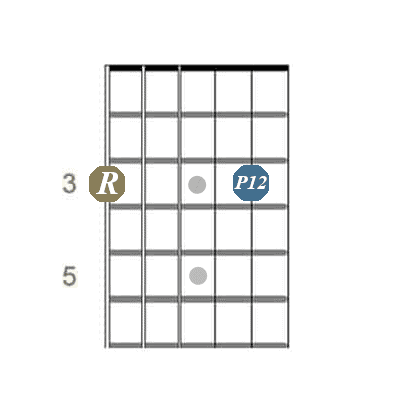

Here’s what a major and minor 9th look like:

Major and minor 10th:

Perfect and augmented 11th:

Perfect 12th:

Intervals And Major/Minor Scales And Chords

Intervals are the building blocks of scales and chords. They are the framework against which scales and chords are built. Different scale and chord interval structures determine the type of scale or chord that is created by playing different notes, whether it is a major scale or a minor scale.

A scale is comprised of melodic intervals with notes played one at a time. Chords are comprised of harmonic intervals played simultaneously. And yes, you can also create a melody out of chords played in succession. A harmonic interval includes notes of varying distances. Just as with chords, the starting note of a scale will determine the name of a scale.

One way to think about the difference between a minor scale and a major scale on the guitar? A major scale always contains a major third note. A minor scale never contains a major third note.

Learning Major Scales and Chords

A major scale consists of seven different notes played one after the other and an octave note, which is the same note occurring 12 semitones above (or below) the starting root note. Guitarists should know major scale patterns and positions.

The ntervals of the major scale: are P1- (2 semitones) – M2 – (2 semitones) – M3 – (1 semitone) – P4 – (2 semitones) – P5 – (2 semitones) – M6 – (2 semitones) – M7- (1 semitone) – P8

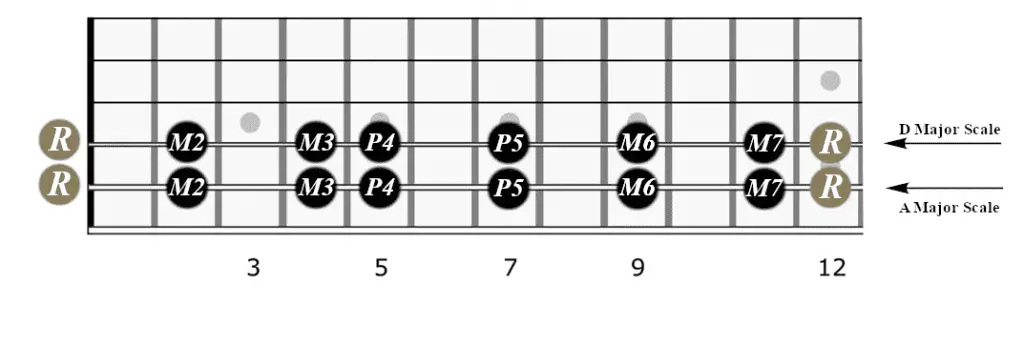

Here is an example of the A major scale and the D major scale, each one played on one string of the guitar. The major scale, regardless of key, has exactly the same interval spacing.

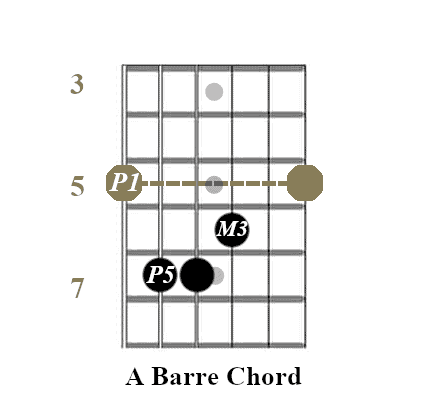

Major chords are constructed with the following intervals: P1 – (4 semitones) – M3 – (3 semitones) – P5. In the Key of A, for instance, the A Major chord is P1 (A) – M3 (C#) – P5 (E).

A major scale and also a major chord have a happy and uplifting sound.

Another type of major scale is the major pentatonic scale. It is a five-note scale, which uses the root, 2nd, 3rd, 5th, and 6th half steps of the major scale, leaving out the 4th and 7th steps.

Here’s how the G major pentatonic looks on a widely used position on the guitar neck:

Learning Minor Scales and Chords

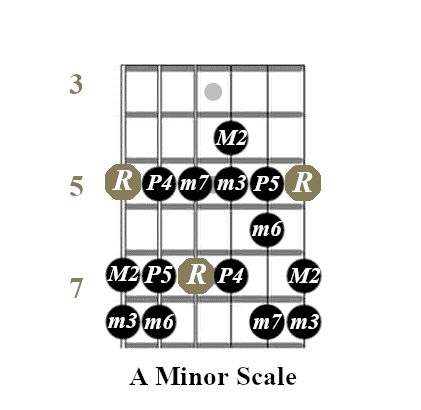

This is the interval structure of a minor scale: P1 – (2 semitones) – M2 – (1 semitone) – m3 – (2 semitones) – P4 – (2 semitones) – P5 – (1 semitone) – m6 – (2 semitones) – m7 – (2 semitone) – P8.

Here is an example of how the C minor scale sounds (piano).

Here’s how the A major scale looks like on a widely used location on the guitar neck, across three octaves:

Note that the minor scale differs from the major scale at the 3rd, 6th, and 7th steps where the intervals are minor rather than major. These differing intervals convey a moody or sad sense in a minor scale as opposed to the brighter, happier sound of major scales.

There are three types of minor scales for guitar: the natural minor scale—which is often referred to simply as the “minor scale,” the structure of which we saw above—the harmonic minor scale, and the melodic minor scale.

The structure of the harmonic minor scale is the same as the natural minor scale, but with a major 7th (M7) instead of a minor 7th (m7).

The melodic minor has the same structure as the natural minor, except for a major 6th (M6) and 7th (M7) when ascending. When descending, it has the exact same structure as the natural minor scale.

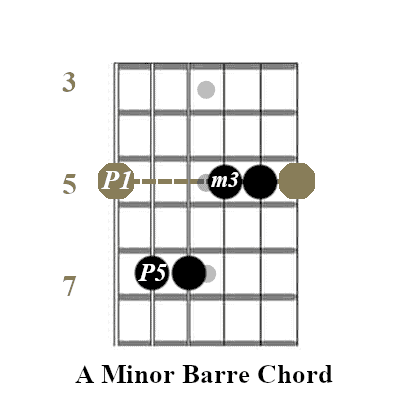

Minor chords are constructed with the following intervals: P1 – (3 semitones) – m3 – (4 semitones) – P5. In the Key of A, for instance, the A minor chord is P1 (A) – m3 (C) – P5 (E).

Working With Blues Scales

Let’s talk about one of the most popular guitar takes on the minor scale.

I’m always impressed by the large number of blues scales, but the most popular is a variation on the minor pentatonic scale. The minor pentatonic intervals

are P1 – (3 semitones ) – m3 – (2 semitones) – P4 – (2 semitones) – P5 – (3 semitones) – m7. The interval between m7 and P8 to complete the octave is not included but understood.

In the Blues Pentatonic scale, a d5 diminished fifth tone is added to give the intervals: P1 – (3 semitones ) – m3 – (2 semitones) – P4 – (1 semitone) – d5 – (1 semitone) – P5 – (3 semitones) – m7. Again the interval between m7 and P8 to complete the octave is not included but understood.

The m3, d5, and m7 are the “Blue” notes that distinguish this scale. All blues guitarists (Hendrix, Clapton, Page, Beck, and others) make extensive use of this scale in their soloing and chordal structures.

Guitar Intervals Exercises

The chart below is your roadmap to the exercises you can do to develop your ability to play intervals and hear what they sound like. You’ll build both muscle memory and hearing memory.

Exercise 1 – Octaves

Starting with the root note shown at the open 6th string (E), play that note followed by each of the other roots shown by R on the diagram. As you play the 2 notes of each interval listen to the sound of the interval. Also, it helps to say aloud the letter name of the note you are playing. This will help you start to learn the pitch of each position on the fretboard.

Exercise 2 – Perfect 4ths

Repeat exercise 1, but this time, move between the Root and the Perfect 4th (shown as P4 in the chart). Again listen to the sound of the interval and say the letter names of the notes aloud.

Exercise 3 – Perfect 5ths

Repeat as above, but this time between the Root and Perfect 5th (P5). Again listen to each interval and say aloud the letter names of the notes you are playing.

More Practice Tips

There are 12 intervals, and practicing each of these as above faithfully will lead to mastery of the fretboard. 3rds and 6ths, both Major and minor, can be good intervals to tackle next. Keep up the great work!

Learning Guitar Intervals For Dummies

The easiest way to describe a guitar interval is the distance from a root note on your guitar, otherwise known as your starting point on the fretboard. You can see what intervals sound like simply by playing from fret to fret along the neck of your guitar.

If you’re looking at your guitar’s neck, let’s look first at the lower E string. If you hold down the first fret, you’ve moved up one semitone or half a step. This is an F. Move to the second fret. This is an F# or Gb. Move to the third fret. This is a G. You can play through the strings and see how you move up through the scale by half steps, fret by fret, and string by string.

When you’re building skills on the guitar, it’s easy to get overwhelmed by all the terminology. Music theory includes intervals, but you do not need to understand advanced music theory to understand intervals and how they can improve your playing and skills.

Some of the terms you should remember as you practice and learn include:

- Interval: the distance between two notes on the guitar.

- Root note: the starting note for an interval.

- Semitone: Also called “half-step” or “half-tone,” which is one fret distance on the guitar.

- Whole tone: Two frets distance on the guitar.

A melodic interval is comprised of two notes played one after another. Melodic intervals form the melody of a song.

A harmonic interval is a set of notes played at the same time, forming a chord. Major and minor chords are made up of different notes that are played at intervals which form either a minor or a major interval structure within the chords.

Ear Training To Practice And Understand Guitar Intervals

Just as playing the shapes of different intervals builds muscle memory, ear training to recognize the sound of the intervals builds hearing memory.

When you can hear in your head the sound of the interval you want to move to, and you know how to locate that note on the guitar fretboard, then you have developed a powerful tool to expand your playing horizons.

Below is a nice ear training tool that I’ve found very useful.

An Excellent Intervals Quiz

To train your ear to hear intervals, check out this excellent intervals quiz.

I also recommend the Interval Fretboard Trainer by Guitar Orb.

There’s also Rick Beato’s awesome ear training course, which is not free but very well worth the investment if you are serious about this whole interval business.

Guitar Intervals PDF

We’ve put together a Guitar Intervals PDF that you can use as a sort of cheat sheet.

Check Out This Band Named Intervals!

Intervals on guitar are the basis of a lot of different styles of guitar music. Progressive rock can sound a bit heavy, and we might expect a progressive metal band to sound heavy, too, but the band Intervals has a light, modern metal sound.

Intervals is a Canadian progressive, guitar-forward metal band led by Aaron Marshall. The band has been together since 2011, releasing their first EPs in 2011 and 2012. As of 2022, they have released four complete albums. The Toronto-based all-instrumental group has a sophisticated sound created by Aaron Marshall’s complex, driving melodies, which take full advantage of the complete fretboard.

Aaron has done his interval homework for sure!

FAQ About Guitar Intervals

Here are some frequently asked questions and answers about learning intervals on the guitar:

Why Should I Learn Intervals On The Guitar?

It’s easy to get comfortable playing certain keys on the guitar, like E, A, and D. Learning Intervals will enable you to break out of playing your favorite keys.

Working on intervals will also introduce you to new locations on the fretboard, giving much more flexibility to your playing and the types of music you can investigate. Harmonic intervals can help you to include new chords or ways to create harmonies. Melodic intervals can help you to master new melodies in different styles, from classical to shredding.

There are 120 locations on the guitar fretboard where we can play a note (6 strings X 20 fret locations, and more if your guitar has more frets!). These 120 locations create the full-color map of the fretboard and all its intervals. Think of how many of these locations your fingers seldom, if ever, visit—maybe about 75% if you’re like me or a lot of other players!

If you think about it, the fretboard map that most of us are playing with is similar to the map Columbus had of the Americas—extremely sketchy at best. It’s comfortable to play the way we always have, but there’s a lot of fun that we’re unlikely to experience unless we give new ideas and techniques a try.

Take a look at some of your favorite players. Chances are they’re all over the neck of their guitar, playing chord progressions and melodic lines that make your mouth water. Players with this kind of flexibility and ability do know how the intervals work on the guitar, and they are able to use them extensively.

It does take time, effort, and practice to learn intervals on the guitar and master the fretboard. I think you’ll be pleased with the good results you’ll have if you move forward with your knowledge of intervals and how the fretboard works. Every player starts out somewhere. Good luck!

What Musical Intervals Separate The Open Strings Of A Guitar?

E (6th string) – Perfect 4th (P4) – A (5th string) – Perfect 4th (P4) – D (4th string) – Perfect 4th (P4) –

G (3rd string) – Major 3rd (M3) – B (2nd string) – Perfect 4th (P4) – E (1st string)

Why Aren’t Guitar Strings Tuned In Even Intervals?

Have you ever wondered why guitar tuning works the way it does? Why aren’t all guitar strings tuned the same way?

The guitar is tuned such that all the major intervals between strings are a Perfect 4th (P4) (E-A, A-D, D-G, B-E) except for the 3rd and 4th strings, separated by a Major 3rd (M3).

If the guitar were to use a tuning of Perfect 4ths all across, the ability to play melodies (leads), arpeggios, and scales would perhaps be faster and more easily movable. But chord stretches, in many cases, would become unreachable for most players.

What we call Standard Tuning is a compromise between single-note playability and the ease with which chord structures can be shaped by the player. Remember, this interval structure pertains to Standard Tuning only. For alternate tunings like drop D, open C, etc., the interval shapes change all over the fretboard because the intervals between the open strings have changed.

How Do You Memorize Intervals On Guitar?

I think a good way to memorize intervals on the guitar is to listen to reference songs that you know well. This way, you can associate all the intervals your ear already knows well. Listening to music you know and playing along can help in understanding intervals even more.

For example, Metallica’s “For Whom The Bell Tolls” has a couple of descending minor 2nd intervals (m2) in its opening melody.

Tritones divide the octave exactly in half. Typically they’re called a diminished 5th (d5) or augmented 4th (a4), but either way, if you know “Even Flow” by Pearl Jam, you’ve heard the tritone in the guitar part and Eddie Vedder’s vocals.